Online first

Bieżący numer

Archiwum

O czasopiśmie

Polityka etyki publikacyjnej

System antyplagiatowy

Instrukcje dla Autorów

Instrukcje dla Recenzentów

Rada Redakcyjna

Komitet Redakcyjny

Recenzenci

Wszyscy recenzenci

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

Kontakt

Bazy indeksacyjne

Klauzula przetwarzania danych osobowych (RODO)

PRACA PRZEGLĄDOWA

Strategie leczenia stwardnienia rozsianego – terapia eskalacyjna i indukcyjna

1

Studenckie Koło Naukowe przy Katedrze i Klinice Neurologii Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Lublinie, Polska

2

Katedra i Klinika Neurologii Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Lublinie, Polska

Autor do korespondencji

Natalia Wolanin

Studenckie Koło Naukowe przy Katedrze i Klinice Neurologii Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Lublinie, Lublin, Polska

Studenckie Koło Naukowe przy Katedrze i Klinice Neurologii Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Lublinie, Lublin, Polska

Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2020;26(4):336-342

SŁOWA KLUCZOWE

stwardnienie rozsianeimmunomodulacjaterapia eskalacyjnaterapia indukcyjnaleczenie stwardnienia rozsianego

DZIEDZINY

STRESZCZENIE

Wprowadzenie i cel pracy:

Stwardnienie rozsiane (SM) jest najczęstszą chorobą demielinizacyjną. Objawy będące wynikiem destrukcji osłonek mielinowych w OUN są bardzo różnorodne. Przyczyna choroby nie jest w pełni poznana. Leczenie dzieli się na objawowe, leczenie rzutów i modyfikujące przebieg SM. Postać oraz aktywność SM determinują wybór modelu leczenia modyfikującego przebieg choroby. Wyróżniamy dwie główne strategie leczenia: eskalacyjną i indukcyjną. Celem pracy jest omówienie tych strategii oraz nowości w tym zakresie.

Opis stanu wiedzy:

Strategia eskalacyjna polega na rozpoczęciu terapii lekami pierwszej linii o znanym i najbardziej bezpiecznym profilu działania, a w przypadku braku lub niewystarczającej odpowiedzi na to leczenie włącza się leki drugiej. Strategia indukcyjna natomiast bywa stosowana u chorych z dużą aktywnością choroby lub jej agresywnym przebiegiem. Polega na rozpoczęciu terapii od silnych immunosupresantów w celu zahamowania postępu choroby, a następnie podtrzymuje się efekty leczenia stosując bezpieczniejsze leki. Do leków modyfikujących przebieg SM zalicza się m.in.: interferony beta, octan glatirameru, teryflunomid, fumaran dimetylu, fingolimod, natalizumab, mitoksantron, alemtuzumab czy okrelizumab

Podsumowanie:

Leczenie modyfikujące przebieg choroby powinno być dobrane indywidualnie do pacjenta. Ważne jest szybkie jego włączenie, ponieważ terapia jest najskuteczniejsza w pierwszych latach choroby, a także dlatego, że SM diagnozowane jest u młodych dorosłych i szybko może prowadzić do niepełnosprawności. Mimo coraz większych możliwości leczenia modyfikującego przebieg SM, nadal potrzebne są dalsze badania nad nowszymi lekami oraz nad skutecznością poszczególnych strategii leczenia.

Stwardnienie rozsiane (SM) jest najczęstszą chorobą demielinizacyjną. Objawy będące wynikiem destrukcji osłonek mielinowych w OUN są bardzo różnorodne. Przyczyna choroby nie jest w pełni poznana. Leczenie dzieli się na objawowe, leczenie rzutów i modyfikujące przebieg SM. Postać oraz aktywność SM determinują wybór modelu leczenia modyfikującego przebieg choroby. Wyróżniamy dwie główne strategie leczenia: eskalacyjną i indukcyjną. Celem pracy jest omówienie tych strategii oraz nowości w tym zakresie.

Opis stanu wiedzy:

Strategia eskalacyjna polega na rozpoczęciu terapii lekami pierwszej linii o znanym i najbardziej bezpiecznym profilu działania, a w przypadku braku lub niewystarczającej odpowiedzi na to leczenie włącza się leki drugiej. Strategia indukcyjna natomiast bywa stosowana u chorych z dużą aktywnością choroby lub jej agresywnym przebiegiem. Polega na rozpoczęciu terapii od silnych immunosupresantów w celu zahamowania postępu choroby, a następnie podtrzymuje się efekty leczenia stosując bezpieczniejsze leki. Do leków modyfikujących przebieg SM zalicza się m.in.: interferony beta, octan glatirameru, teryflunomid, fumaran dimetylu, fingolimod, natalizumab, mitoksantron, alemtuzumab czy okrelizumab

Podsumowanie:

Leczenie modyfikujące przebieg choroby powinno być dobrane indywidualnie do pacjenta. Ważne jest szybkie jego włączenie, ponieważ terapia jest najskuteczniejsza w pierwszych latach choroby, a także dlatego, że SM diagnozowane jest u młodych dorosłych i szybko może prowadzić do niepełnosprawności. Mimo coraz większych możliwości leczenia modyfikującego przebieg SM, nadal potrzebne są dalsze badania nad nowszymi lekami oraz nad skutecznością poszczególnych strategii leczenia.

Introduction and objective:

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease. The symptoms resulting from the destruction of the myelin sheaths in the CNS are very diverse. The cause of the disease is not fully understood. Treatment can be divided into symptomatic, relapse treatment and MS modifying treatment. The type and activity of MS determine the choice of a disease-modifying treatment model. There are two main treatment strategies: escalation and induction. The aim of the study is to discuss these strategies and new developments in this area.

State of knowledge:

The escalation strategy consists in initiating therapy with first-line drugs with a known and safest profile of action, and in the absence or obtaining an insufficient response to this treatment, second line drugs are introduced successively. The induction strategy, on the other hand, is sometimes used in patients with high disease activity or its aggressive course. It consists in starting the therapy with strong immunosuppressants in order to inhibit the progress of the disease, and then the effects of the treatment are maintained using safer drugs. The drugs modifying the course of MS include interferons beta, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, natalizumab, mitoxantrone, alemtuzumab, or ocrelizumab.

Conclusions:

Disease-modifying treatments should be individualized for each patient. It is important to activate it quickly, because treatment is most effective in the first years of the disease, and also because MS is diagnosed in young adults and can quickly lead to disability. Despite the increasing possibilities of MS modifying treatments, more research is still needed on newer drugs and the effectiveness of treatment strategies.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease. The symptoms resulting from the destruction of the myelin sheaths in the CNS are very diverse. The cause of the disease is not fully understood. Treatment can be divided into symptomatic, relapse treatment and MS modifying treatment. The type and activity of MS determine the choice of a disease-modifying treatment model. There are two main treatment strategies: escalation and induction. The aim of the study is to discuss these strategies and new developments in this area.

State of knowledge:

The escalation strategy consists in initiating therapy with first-line drugs with a known and safest profile of action, and in the absence or obtaining an insufficient response to this treatment, second line drugs are introduced successively. The induction strategy, on the other hand, is sometimes used in patients with high disease activity or its aggressive course. It consists in starting the therapy with strong immunosuppressants in order to inhibit the progress of the disease, and then the effects of the treatment are maintained using safer drugs. The drugs modifying the course of MS include interferons beta, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, natalizumab, mitoxantrone, alemtuzumab, or ocrelizumab.

Conclusions:

Disease-modifying treatments should be individualized for each patient. It is important to activate it quickly, because treatment is most effective in the first years of the disease, and also because MS is diagnosed in young adults and can quickly lead to disability. Despite the increasing possibilities of MS modifying treatments, more research is still needed on newer drugs and the effectiveness of treatment strategies.

Wolanin N, Kamieniak M, Jarosz P, Kobiałka I, Kośmider K, Petit V, Rejdak K. Strategie leczenia stwardnienia rozsianego – terapia eskalacyjna

i indukcyjna. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2020; 26(4): 336–342. doi: 10.26444/monz/130448

REFERENCJE (51)

1.

Kamm CP, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH. Multiple sclerosis: current knowledge and future outlook. Eur Neurol. 2014; 72(3–4): 132–141. doi: 10.1159/000360528.

2.

Benito-León J. Are the prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis changing? Neuroepidemiology. 2011; 36(3): 148–149. doi: 10.1159/000325368.

3.

Klocke S, Hahn N. Multiple sclerosis. Ment Health Clin. 2019; 9(6): 349–358. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2019.11.349.

4.

Cree BA, Gourraud PA, Oksenberg JR i wsp. Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol. 2016; 80(4): 499–510. doi: 10.1002/ana.24747.

5.

Mulero P, Midaglia L, Montalban X. Ocrelizumab: a new milestone in multiple sclerosis therapy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018; 11: 1756286418773025. doi: 10.1177/1756286418773025.

6.

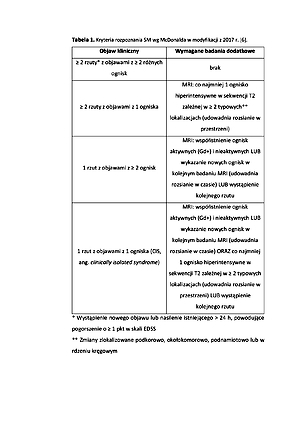

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F i wsp. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018; 17(2): 162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2.

7.

Kamińska J, Koper OM, Piechal K i wsp. Stwardnienie rozsiane – etiopatogeneza i możliwości diagnostyczne. Postepy Hig Med Dosw. 2017; 71: 551–563.

8.

Sicotte NL. Magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis: the role of conventional imaging. Neurol Clin. 2011; 29(2): 343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2011.01.005.

9.

Rudick RA, Whitaker JN. Cerebrospinal fluid tests for multiple sclerosis. W: P Scheinberg (red.). Neurology/neurosurgery updata series, 1987; 7.

10.

Kurtzke JF. A new scale for evaluating disability in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1955; 5(8): 580–583.

11.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983; 33(11): 1444–1452.

12.

Bejer A, Ziemba J. Quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis and degree of motor disability – preliminary report. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2015; 21(4): 402–407. doi: 10.5604/20834543.1186914.

13.

Filippini G, Del Giovane C, Vacchi L i wsp. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; (6): CD008933. Published 2013 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008933.pub2.

14.

Tramacere I, Del Giovane C, Salanti G i wsp. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (9): CD011381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011381.pub2.

15.

Giovannoni G. Disease-modifying treatments for early and advanced multiple sclerosis: a new treatment paradigm. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018; 31(3): 233–243. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000561.

16.

Le Page E, Edan G. Induction or escalation therapy for patients with multiple sclerosis? Rev Neurol. 2018; 174(6): 449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2018.04.004.

17.

Fenu G, Lorefice L, Frau F i wsp. Induction and escalation therapies in multiple sclerosis. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2015; 14(1): 26–34. doi: 10.2174/1871523014666150504122220.

18.

Freedman MS, Selchen D, Prat A i wsp. Managing Multiple Sclerosis: Treatment Initiation, Modification, and Sequencing. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018; 45(5): 489–503. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2018.17.

19.

Merkel B, Butzkueven H, Traboulsee AL i wsp. Timing of high-efficacy therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2017; 16(6): 658–665. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.04.010.

20.

D’Amico E, Ziemssen T, Cottone S. Induction therapy for the management of early relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. A critical opinion. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017; 18(15): 1553-1556. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1367383.

21.

Ruggieri S, Pontecorvo S, Tortorella C i wsp. Induction treatment strategy in multiple sclerosis: a review of past experiences and future perspectives. Mult Scler Demyelinating Disord. 2018; 3(5). doi: 10.1186/s40893-018-0037-7.

22.

Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F. Pulsed immune reconstitution therapy in multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019; 12: 1756286419836913. doi: 10.1177/1756286419836913.

23.

Załączniki do obwieszczenia Ministra Zdrowia w sprawie wykazu refundowanych leków, środków spożywczych specjalnego przeznaczenia żywieniowego oraz wyrobów medycznych dostępne na stronie: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie... (dostęp: 11.11.2020).

24.

Rommer PS, Milo R, Han MH i wsp. Immunological Aspects of Approved MS Therapeutics. Front Immunol. 2019; 10: 1564. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01564.

25.

Kułakowska A, Drozdowski W. Leczenie interferonami beta i octanem glatirameru a spowolnienie progresji niesprawności u chorych na stwardnienie rozsiane. Pol Przegl Neurol. 2014; 10(4): 145–156.

26.

Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA i wsp. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG) [published correction appears in Ann Neurol. 1996 Sep; 40(3): 480]. Ann Neurol. 1996; 39(3): 285–294. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390304.

27.

Losy J, Bartosik-Psujek H, Członkowska A i wsp. Leczenie stwardnienia rozsianego Zalecenia Polskiego Towarzystwa Neurologicznego, Pol Przegl Neurol. 2016; 12(2): 80–95.

28.

Wynn DR. Enduring Clinical Value of Copaxone® (Glatiramer Acetate) in Multiple Sclerosis after 20 Years of Use. Mult Scler Int. 2019; 2019: 7151685. doi: 10.1155/2019/7151685.

29.

Dubey D, Kieseier BC, Hartung HP i wsp. Dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: rationale, mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015; 15(4): 339–346. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1025755.

30.

Bomprezzi R. Dimethyl fumarate in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an overview. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2015; 8(1): 20–30. doi: 10.1177/1756285614564152.

31.

Oh J, O’Connor PW. Teriflunomide in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: current evidence and future prospects. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2014; 7(5): 239–252. doi: 10.1177/1756285614546855.

32.

Aly L, Hemmer B, Korn T. From Leflunomide to Teriflunomide: Drug Development and Immunosuppressive Oral Drugs in the Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017; 15(6): 874–891. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666161208151525.

33.

Bartosik-Psujek H, Selmaj K. Fingolimod w leczeniu stwardnienia rozsianego – aspekty praktyczne. Pol Przegl Neurol. 2015; 11(1): 36–43.

34.

Ziemssen T, Medin J, Couto CA i wsp. Multiple sclerosis in the real world: A systematic review of fingolimod as a case study. Autoimmun Rev. 2017; 16(4): 355–376. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.02.007.

35.

Vollmer BL, Nair KV, Sillau S i wsp. Natalizumab versus fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis treatment. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018; 6: 252–262.

36.

Palasik W. Leki biologiczne w leczeniu stwardnienia rozsianego. Przegląd aktualnych osiągnięć. Biological treatment in multiple sclerosis. Review current development. Post N Med. 2013; 10: 715–719.

37.

Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E i wsp. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(9): 899–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044397.

38.

Edan G, Miller D, Clanet M i wsp. Therapeutic effect of mitoxantrone combined with methylprednisolone in multiple sclerosis: a randomised multicenter study of active disease using MRI and clinical criteria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997; 62: 112–8.

39.

Vollmer T, Panitch H, Bar-Or A i wsp. Glatiramer acetate after induction therapy with mitoxantrone in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008; 14(5): 663–670. doi: 10.1177/1352458507085759.

40.

Edan G, Comi G, Le Page E i wsp. Mitoxantrone prior to interferon beta-1b in aggressive relapsing multiple sclerosis: a 3-year randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011; 82(12): 1344–1350. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.229724.

41.

Edan G, Le Page E. Induction therapy for patients with multiple sclerosis: why? When? How? CNS Drugs. 2013; 27(6): 403–409. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0065-y.

42.

Jacobs BM, Ammoscato F, Giovannoni G i wsp. Cladribine: mechanisms and mysteries in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018; 89(12): 1266–1271. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317411.

43.

Giovannoni G. Cladribine to Treat Relapsing Forms of Multiple Sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2017; 14(4): 874–887. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0573-4.

44.

Robles-Cedeno R, Ramio-Torrenta L. Cladribina en el tratamiento de la esclerosis multiple recurrente [Cladribine in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis]. Rev Neurol. 2018; 67(9): 343–354.

45.

Comi G, Hartung HP, Kurukulasuriya NC i wsp. Cladribine tablets for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013; 14(1): 123–136. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.754012.

46.

Potemkowski A. Stwardnienie rozsiane w świecie i w Polsce – ocena epidemiologiczna. Aktualn Neurol. 2009; 9(2): 91–97.

47.

Stankiewicz JM, Weiner HL. An argument for broad use of high efficacy treatments in early multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019; 7(1): e636. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000636.

48.

Kremer D, Göttle P, Flores-Rivera J i wsp. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis: from concept to clinical trials. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019; 32(3): 378–384. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000692.

49.

Cadavid D, Balcer L, Galetta S i wsp. Safety and efficacy of opicinumab in acute optic neuritis (RENEW): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017; 16(3): 189–199. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30377-5.

50.

Ruggieri S, Tortorella C, Gasperini C. Anti lingo 1 (opicinumab) a new monoclonal antibody tested in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017; 17(11): 1081–1089. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1378098.

51.

Cadavid D, Mellion M, Hupperts R i wsp. Safety and efficacy of opicinumab in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (SYNERGY): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019; 18(9): 845–856. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30137-1.

Przetwarzamy dane osobowe zbierane podczas odwiedzania serwisu. Realizacja funkcji pozyskiwania informacji o użytkownikach i ich zachowaniu odbywa się poprzez dobrowolnie wprowadzone w formularzach informacje oraz zapisywanie w urządzeniach końcowych plików cookies (tzw. ciasteczka). Dane, w tym pliki cookies, wykorzystywane są w celu realizacji usług, zapewnienia wygodnego korzystania ze strony oraz w celu monitorowania ruchu zgodnie z Polityką prywatności. Dane są także zbierane i przetwarzane przez narzędzie Google Analytics (więcej).

Możesz zmienić ustawienia cookies w swojej przeglądarce. Ograniczenie stosowania plików cookies w konfiguracji przeglądarki może wpłynąć na niektóre funkcjonalności dostępne na stronie.

Możesz zmienić ustawienia cookies w swojej przeglądarce. Ograniczenie stosowania plików cookies w konfiguracji przeglądarki może wpłynąć na niektóre funkcjonalności dostępne na stronie.