RESEARCH PAPER

Consumption of snacks and sweetened beverages and physical activity of schoolchildren aged 10–16 years

1

Studenckie Koło Naukowe Młodych Edukatorów, Zakład Żywienia Człowieka, Katedra Dietetyki, Wydział Zdrowia Publicznego w Bytomiu, Śląski Uniwersytet Medyczny w Katowicach, Polska

2

Wydział Ochrony Zdrowia, Śląska Wyższa Szkoła Medyczna w Katowicach, Polska

3

Katedra i Zakład Podstawowych Nauk Medycznych, Wydział Zdrowia Publicznego w Bytomiu, Szkoła Doktorska

Śląskiego Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Katowicach, Polska

4

Zakład Żywienia Człowieka, Katedra Dietetyki, Wydział Zdrowia Publicznego w Bytomiu, Śląski Uniwersytet Medyczny

w Katowicach, Polska

Corresponding author

Marika Wlazło

Studenckie Koło Naukowe Młodych Edukatorów, Zakład Żywienia Człowieka, Katedra Dietetyki, Wydział Zdrowia Publicznego w Bytomiu, Śląski Uniwersytet Medyczny w Katowicach

Studenckie Koło Naukowe Młodych Edukatorów, Zakład Żywienia Człowieka, Katedra Dietetyki, Wydział Zdrowia Publicznego w Bytomiu, Śląski Uniwersytet Medyczny w Katowicach

Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2023;29(3):240-249

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objective:

Children and adolescents are a group particularly exposed to nutritional consequences resulting from the consumption of potentially harmful food products. School-age children should eat 5 meals a day with 3–4 hour breaks between meals. It is also acceptable to eat snacks, however attention should be paid that they provide health-promoting ingredients. The aim of the study is assessment of the frequency of consumption of snacks and sweetened beverages and physical activity by children and adolescents at school age, and determination whether there are any relationships between the age of the surveyed schoolchildren and the frequency of consumption of snacks and sweetened beverages.

Material and methods:

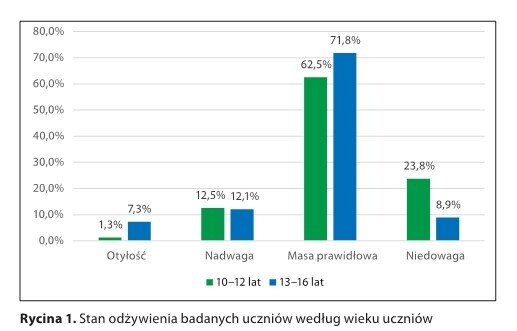

The study was conducted in 2022 among 204 schoolchildren aged 13–16 attending primary schools in the Silesian agglomeration. The research tool was an author-constructed questionnaire. To determine the value of the body mass index of the surveyed schoolchildren the OLA and OLAF charts for children and adolescents aged 3–18 were used. Statistical analysis was performed by means of Statistica 13.3 using the Student’s t-test and chi2 test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

Shoolchildren aged 10–12 most often reached for snacks while watching TV (25.5%), while those aged 13–16 while using a computer (20.1%). Chocolate, chocolate bars, cakes, biscuits, gummies, chocolate creams, candies and confectionery were consumed most often several times a month.

Conclusions:

Consumption of snacks by children and adolescents during the day is a frequent problem. Both age groups are characterized by snacking while spending leisure time passively, which is also associated with an insufficient level of physical activity undertaken by them.

Children and adolescents are a group particularly exposed to nutritional consequences resulting from the consumption of potentially harmful food products. School-age children should eat 5 meals a day with 3–4 hour breaks between meals. It is also acceptable to eat snacks, however attention should be paid that they provide health-promoting ingredients. The aim of the study is assessment of the frequency of consumption of snacks and sweetened beverages and physical activity by children and adolescents at school age, and determination whether there are any relationships between the age of the surveyed schoolchildren and the frequency of consumption of snacks and sweetened beverages.

Material and methods:

The study was conducted in 2022 among 204 schoolchildren aged 13–16 attending primary schools in the Silesian agglomeration. The research tool was an author-constructed questionnaire. To determine the value of the body mass index of the surveyed schoolchildren the OLA and OLAF charts for children and adolescents aged 3–18 were used. Statistical analysis was performed by means of Statistica 13.3 using the Student’s t-test and chi2 test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

Shoolchildren aged 10–12 most often reached for snacks while watching TV (25.5%), while those aged 13–16 while using a computer (20.1%). Chocolate, chocolate bars, cakes, biscuits, gummies, chocolate creams, candies and confectionery were consumed most often several times a month.

Conclusions:

Consumption of snacks by children and adolescents during the day is a frequent problem. Both age groups are characterized by snacking while spending leisure time passively, which is also associated with an insufficient level of physical activity undertaken by them.

REFERENCES (52)

1.

Ferenc P, Traczyk I, Panczyk M. Wybory żywieniowe dzieci szóstych i siódmych klas szkół podstawowych na podstawie zakupów dokonywanych w sklepikach szkolnych oraz w drodze do/ze szkoły. Bromat Chem Toksykol. 2018;2(51):145–153.

2.

Szczepańska E, Bielaszka A, Kiciak A. et al. The Project “Colourful Means Healthy” as an Educational Measure for the Prevention of Diet-Related Diseases: Investigating the Impact of Nutrition Education for School-Aged Children on Their Nutritional Knowledge. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19:13307.

4.

Wolnicka K. Talerz zdrowego żywienia. Talerz zdrowego żywienia – Narodowe Centrum Edukacji Żywieniowej (pzh.gov.pl) (access: 2023.04.03).

5.

Lesiów T, Kuchlewska M. Rola przekąsek w żywieniu człowieka ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem przekąsek mięsnych. Nauki inżynierskie i technologie. 2020;1(36):113–126.

6.

Decyk-Chęcel A. Zwyczaje żywieniowe dzieci i młodzieży. Probl Hig Epidemiol. 2017;98(2):103–109.

7.

Suleiman-Martos N, García-Lara RA, Martos-Cabrera MB, et al. Gamification for the Improvement of Diet, Nutritional Habits, and Body Composition in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2021;13(7):2478.

8.

Caroppo E, Mazza M, Sannella A, et al. Will Nothing Be the Same Again?: Changes in Lifestyle during COVID-19 Pandemic and Consequences on Mental Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8433.

9.

Basiak-Rasała A, Górna S, Krajewska J, et al. Nutritional habits according to age and BMI of 6–17-year-old children from the urban municipality in Poland. J Health Popul Nutr. 2022;41(1):17.

10.

Moss RH, Conner M, O'Connor DB. Exploring the effects of positive and negative emotions on eating behaviours in children and young adults. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26(4):457–466.

11.

Guzek D, Głąbska D, Groele B, et al. Role of fruit and vegetables for the mental health of children: a systematic review. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2020;71(1):5–13.

12.

Maleki SJ, Crespo JF, Cabanillas B. Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids. Food Chem. 2019;30(299):125124.

13.

Dreher ML. Whole Fruits and Fruit Fiber Emerging Health Effects. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1833.

14.

Alasalvar C, Salvadó JS, Ros E. Bioactives and health benefits of nuts and dried fruits. Food Chem. 2020;314:126192.

15.

de Lamas C, de Castro MJ, Gil-Campos M, et al. Effects of Dairy Product Consumption on Height and Bone Mineral Content in Children: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(2):88–96.

16.

Febbraio MA, Karin M. „Sweet death”: Fructose as a metabolic toxin that targets the gut-liver axis. Cell Metab. 2021;33(12):2316–2328.

17.

Vlachos D, Malisova S, Lindberg FA, et al. Glycemic Index (GI) or Glycemic Load (GL) and Dietary Interventions for Optimizing Postprandial Hyperglycemia in Patients with T2 Diabetes: A Review. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1561.

18.

Moussa M, Hansz K, Rasmussen M, et al. Cardiovascular Effects of Energy Drinks in the Pediatric Population. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(11):578–582.

19.

Pérez-Gimeno G, Rupérez AI, Vázquez-Cobela R, et al. Energy Dense Salty Food Consumption Frequency Is Associated with Diastolic Hypertension in Spanish Children. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1027.

20.

Szczepańska E, Białek-Dratwa A, Janota, B, et al. Dietary Therapy in Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) – Tradition or Modernity? A Review of the Latest Approaches to Nutrition in CVD. Nutrients. 2022;14(13):2649.

21.

Cornwell B, Villamor E, Mora-Plazas M, et al. Processed and ultra-processed foods are associated with lower-quality nutrient profiles in children from Colombia. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(1):142–147.

22.

Perera DN, Hewavitharana GG, Navaratne SB. Comprehensive Study on the Acrylamide Content of High Thermally Processed Foods. Biomed Res Int. 2021:6258508.

23.

Halicka E, Kaczorowska J, Rejman K, et al. Parental Food Choices and Engagement in Raising Children‘s Awareness of Sustainable Behaviors in Urban Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3225.

24.

Scaglioni S, De Cosmi V, Ciappolino V, et al. Factors Influencing Children‘s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):706.

25.

Wojtyła-Buciora P, Żukiewicz-Sobczak W, Wojtyła K, et al. Sposób żywienia uczniów szkół podstawowych w powiecie kaliskim – w opinii dzieci i ich rodziców. Probl Hig Epidemiol. 2015;96(1):245–253.

26.

Szczyrba A. „Nawyki i preferencje żywieniowe dzieci i młodzieży z ,Zespołu Pieśni i Tańca Częstochowa'”. Nauki Przyrodnicze i Medyczne. 2021;32(2):13–27.

27.

Kocka K, Bartoszek A, Fus M, et al. Nawyki żywieniowe i aktywność fizyczna młodzieży szkół ponadgimnazjalnych jako czynniki ryzyka wystąpienia otyłości. J Educ Health Sport. 2016;6:439–452.

28.

Szczepańska E, Janota B, Janion K. Selected life style elements In adolescents attending high school. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2020;71(2):147–156.

29.

Michalak A. Ocena stanu odżywienia i nawyków żywieniowych młodzieży szkoły podstawowej w aspekcie ryzyka wybranych chorób cywilizacyjnych. Innowacje w Pielęgniarstwie i Naukach o Zdrowiu. 2022;7(1):25–50.

30.

Rafieifar S, Pouraram H, Djazayery A, et al. Strategies and Opportunities Ahead to Reduce Salt Intake. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(10):729–734.

31.

Marangoni F, Martini D, Scaglioni S, et al. Snacking in nutrition and health. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2019;70(8):909–923.

32.

Kosicka-Gębska M, Gębski J. Słone przekąski w diecie młodych konsumentów. Bromat Chem Toksykol. 2012;3(45):733–738.

33.

Urbańska I, Czarniecka-Skubina E. Częstotliwość spożycia przez młodzież produktów spożywczych oferowanych w sklepikach szkolnych. ŻYWNOŚĆ. Nauka. Technologia. Jakość. 2007;3(52):193–204.

34.

Jasińska M. Nawyki żywieniowe młodzieży gimnazjalnej ze środowiska miejskiego i wiejskiego. Lubelski Rocznik Pedagogiczny. 2013;32:35–68.

35.

Pysz K, Leszczyńska T, Kopeć A. Assessment of the Frequency of snack and beverages consumption and stimulants intake in children grown up in orphanages in Krakow. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2015;66(2):151–158.

36.

Ciesińska A. Nawyki żywieniowe łódzkich gimnazjalistów. Pielęgniarstwo Polskie. 2017;65(3):437–442. http://dx.doi.org/10.20883/pie....

37.

Duś Z, Gośliński M, Nowak D. Analiza spożycia warzyw, owoców i soków w grupie uczniów szkoły podstawowej. In: Problemy społeczne w XXI wieku – przegląd badań. Lublin: TYGIEL; 2020. p. 61–72.

38.

Cichocka I, Krupa J. Nawyki żywieniowe młodzieży ze szkół ponadgimnazjalnych z terenu Nowego Sącza. Handel Wewnętrzny. 2017;6(371):41–55.

39.

Miller C, Ettridge K, Wakefield M, et al. Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Juice, Artificially-Sweetened Soda and Bottled Water: An Australian Population Study. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):817.

40.

Macintyre AK, Marryat L, Chambers S. Exposure to liquid sweetness in early childhood: artificially-sweetened and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption at 4–5 years and risk of overweight and obesity at 7–8 years. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13:755–765.

41.

Ahn H, Park YK. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr J. 2021;20(1):41.

42.

Farhangi MA, Nikniaz L, Khodarahmi M. Sugar-sweetened beverages increases the risk of hypertension among children and adolescence: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):344.

43.

Anderson JJ, Gray SR, Welsh P, et al. The associations of sugar-sweetened, artificially sweetened and naturally sweet juices with all-cause mortality in 198,285 UK Biobank participants: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):97.

44.

Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Steltz SK, et al. Effects of Sugar-Sweetened, Artificially Sweetened, and Unsweetened Beverages on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors, Body Composition, and Sweet Taste Preference: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015668.

45.

Borges MC, Louzada ML, de Sá TH, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages and the response to the global obesity crisis. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002195.

46.

Książyk J, Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz A, Toporowska-Kowalska E, et al. Woda i napoje w żywieniu dzieci. Zalecenia Polskiego Towarzystwa Żywienia Klinicznego Dzieci. Standardy Medyczne Pediatria. 2021;18:529–533.

47.

Ambroży J, Bester J, Czuchraj W, et al. Eating habits and frequency of consumption of selected products among children aged 10–13 years residing in urban and rural areas. Ann Acad Med Siles. 2013;67(4):231–237.

48.

Piórecka B, Kozioł-Kozakowska A, Jagielski P, et al. Częstotliwość oraz wybory dotyczące spożycia płynów w grupie dzieci i młodzieży szkolnej z Niepołomic i Krakowa. Bromat Chem Toksykol. 2019;2(52):168–174.

49.

Gage R, Girling-Butcher M, Joe E, et al. The Frequency and Context of Snacking among Children: An Objective Analysis Using Wearable Cameras. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):103.

50.

Stasiuk J, Kułak W, Lankau A. Aktywność fizyczna młodzieży a częstość korzystania z telefonów. In: Lankau A, Krajewska-Kułak E. Sytuacje trudne w ochronie zdrowia, Białystok: 2021. p. 473–501.

51.

Pilewska-Kozak AB, Łepecka-Klusek C, Grażyna S, et al. Aktywność fizyczna dziewcząt w okresie dojrzewania. J Educ Health Sport. 2015;5(9):305–316.

52.

Kaczor-Szkodny P, Horoch CA, Kulik TB, et al. Aktywność fizyczna i formy spędzania czasu wolnego wśród uczniów w wieku 12–15 lat. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2016;22(2):113–119.

Share

RELATED ARTICLE

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.