Online first

Bieżący numer

Archiwum

O czasopiśmie

Polityka etyki publikacyjnej

System antyplagiatowy

Instrukcje dla Autorów

Instrukcje dla Recenzentów

Rada Redakcyjna

Komitet Redakcyjny

Recenzenci

Wszyscy recenzenci

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

Kontakt

Bazy indeksacyjne

Klauzula przetwarzania danych osobowych (RODO)

PRACA PRZEGLĄDOWA

Interwencja antynikotynowa a e-papierosy i podgrzewacze tytoniu – o czym należy pamiętać? Rekomendacje dla lekarzy

praktyków mających bezpośredni kontakt z pacjentem uzależnionym od nikotyny w zakresie interwencji antynikotynowej

1

Katedra Higieny i Epidemiologii, Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi, Polska

2

Starostwo Powiatowe w Piotrkowie Trybunalskim, Polska

3

Zakład Zdrowia Populacyjnego, Szkoła Zdrowia Publicznego, Centrum Medyczne Kształcenia Podyplomowego, Polska

4

Sekcja Antytytoniowa, Polskie Towarzystwo Chorób Płuc, Polska

Autor do korespondencji

Beata Świątkowska

Katedra Higieny i Epidemiologii, Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi, Żeligowskiego 7/9, 90-752, Łódź, Polska

Katedra Higieny i Epidemiologii, Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi, Żeligowskiego 7/9, 90-752, Łódź, Polska

Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2024;30(2):81-86

SŁOWA KLUCZOWE

DZIEDZINY

STRESZCZENIE

Wprowadzenie i cel:

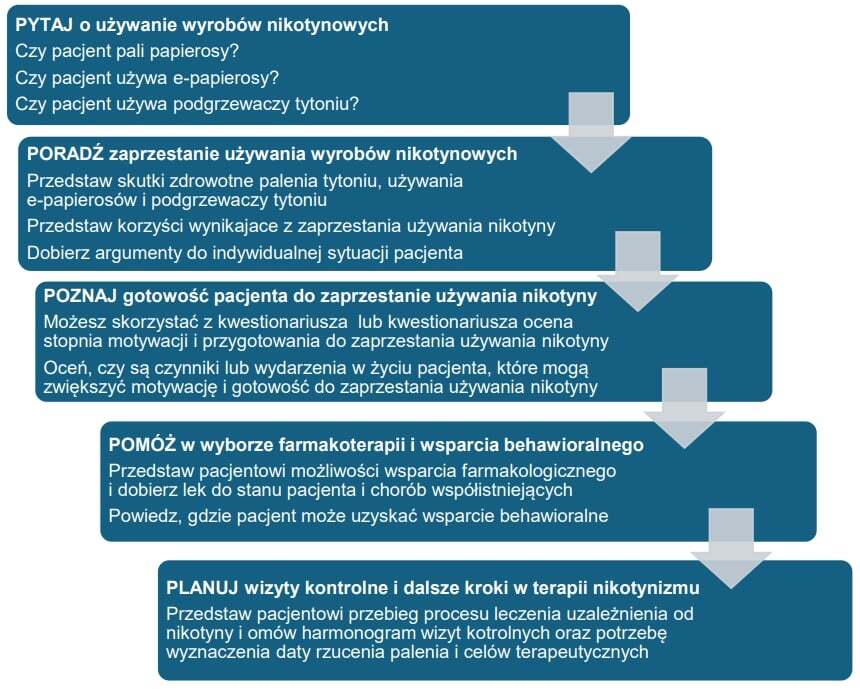

Rynek wyrobów nikotynowych uległ dynamicznej zmianie. Wprowadzenie nowych form wyrobów nikotynowych, takich jak papierosy elektroniczne (e-papierosy) i systemy podgrzewające tytoń, implikuje konieczność weryfikacji dotychczasowego poradnictwa antynikotynowego realizowanego przez personel medyczny. Celem pracy było omówienie wpływu e-papierosów i podgrzewaczy tytoniu na realizację działań z zakresu minimalnej interwencji antynikotynowej (zasada 5P) przez lekarzy praktyków mających bezpośredni kontakt z pacjentem palącym w Polsce.

Metody przeglądu:

Publikacja ma charakter przeglądu narracyjnego. Do przeglądu piśmiennictwa użyto bazy PubMed/ Medline. W pracy przedstawiono rekomendacje dotyczące konieczności modyfikacji postępowania z pacjentem uzależnionym od nikotyny dostarczanej m.in. za pomocą e-papierosów i podgrzewaczy tytoniu w odniesieniu do dotychczas obowiązujący chstandardów minimalnej interwencji antytytoniowej, opartej na zasadzie 5P.

Opis stanu wiedzy:

E-papierosy i podgrzewacze tytoniu stanowią nową formę dostarczania nikotyny do organizmu. Nikotyna ma silny potencjał uzależniający. Aerozol z e-papierosa lub podgrzewacza tytoniu jest szkodliwy dla zdrowia. Użytkownik e-papierosa lub podgrzewacza tytoniu powinien być traktowany jak osoba uzależniona od nikotyny i objęty tymi samymi interwencjami antynikotynowymi co palacze papierosów.

Podsumowanie:

Szczególnie ważna w realizacji działań antynikotynowych jest właściwa identyfikacja osób uzależnionych od nikotyny, odnotowanie informacji na temat uzależnienia od nikotyny i sposobu przyjmowania nikotyny w dokumentacji medycznej pacjenta oraz zapewnienie mu podstawowego wsparcia behawioralnego oraz farmakoterapii wspierającej leczenie uzależnienia od nikotyny, niezależnie od tego, czy nikotyna przyjmowana jest w formie papierosa, e-papierosa czy podgrzewacza tytoniu.

Rynek wyrobów nikotynowych uległ dynamicznej zmianie. Wprowadzenie nowych form wyrobów nikotynowych, takich jak papierosy elektroniczne (e-papierosy) i systemy podgrzewające tytoń, implikuje konieczność weryfikacji dotychczasowego poradnictwa antynikotynowego realizowanego przez personel medyczny. Celem pracy było omówienie wpływu e-papierosów i podgrzewaczy tytoniu na realizację działań z zakresu minimalnej interwencji antynikotynowej (zasada 5P) przez lekarzy praktyków mających bezpośredni kontakt z pacjentem palącym w Polsce.

Metody przeglądu:

Publikacja ma charakter przeglądu narracyjnego. Do przeglądu piśmiennictwa użyto bazy PubMed/ Medline. W pracy przedstawiono rekomendacje dotyczące konieczności modyfikacji postępowania z pacjentem uzależnionym od nikotyny dostarczanej m.in. za pomocą e-papierosów i podgrzewaczy tytoniu w odniesieniu do dotychczas obowiązujący chstandardów minimalnej interwencji antytytoniowej, opartej na zasadzie 5P.

Opis stanu wiedzy:

E-papierosy i podgrzewacze tytoniu stanowią nową formę dostarczania nikotyny do organizmu. Nikotyna ma silny potencjał uzależniający. Aerozol z e-papierosa lub podgrzewacza tytoniu jest szkodliwy dla zdrowia. Użytkownik e-papierosa lub podgrzewacza tytoniu powinien być traktowany jak osoba uzależniona od nikotyny i objęty tymi samymi interwencjami antynikotynowymi co palacze papierosów.

Podsumowanie:

Szczególnie ważna w realizacji działań antynikotynowych jest właściwa identyfikacja osób uzależnionych od nikotyny, odnotowanie informacji na temat uzależnienia od nikotyny i sposobu przyjmowania nikotyny w dokumentacji medycznej pacjenta oraz zapewnienie mu podstawowego wsparcia behawioralnego oraz farmakoterapii wspierającej leczenie uzależnienia od nikotyny, niezależnie od tego, czy nikotyna przyjmowana jest w formie papierosa, e-papierosa czy podgrzewacza tytoniu.

Introduction and objective:

The market for nicotine products has changed dynamically. The introduction of new forms of nicotine products, such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and heated tobacco products implies the need for verification of the current anti-smoking counseling provided by medical staff. The aim of the study was to discuss the impact of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco on the implementation of actions in the area of brief anti-smoking intervention ("5A principle") by medical practitioners who have direct contact with patients addicted to nicotine in Poland.

Review methods:

This is a narrative review. The PubMed/Medline database was used to review the literature. The publication presents recommendations regarding the need to modify the treatment of a patient addicted to nicotine supplied, among others, by using e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products, with reference to the existing standards of brief anti-smoking intervention, based on the 5A principle.

Abbreviated description of the state of knowledge:

E-cigarettes and heated tobacco products are a new form of delivering nicotine to the human body. Nicotine has a strong addictive potential. Aerosol from an e-cigarette or heated tobacco product is harmful to health. The user of an e-cigarette or heated tobacco product should be treated as a person addicted to nicotine and subject to the same anti-smoking interventions as cigarette smokers.

Summary:

While implementing anti-smoking interventions it is very important to properly identify people addicted to nicotine, record information on nicotine addiction and the way of taking nicotine in the patient'smedical records, and provide basic behavioural support and pharmacotherapy to support the treatment of nicotine addiction, regardless of the form of nicotine intake – cigarettes, e-cigarette or heated tobacco products.

The market for nicotine products has changed dynamically. The introduction of new forms of nicotine products, such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and heated tobacco products implies the need for verification of the current anti-smoking counseling provided by medical staff. The aim of the study was to discuss the impact of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco on the implementation of actions in the area of brief anti-smoking intervention ("5A principle") by medical practitioners who have direct contact with patients addicted to nicotine in Poland.

Review methods:

This is a narrative review. The PubMed/Medline database was used to review the literature. The publication presents recommendations regarding the need to modify the treatment of a patient addicted to nicotine supplied, among others, by using e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products, with reference to the existing standards of brief anti-smoking intervention, based on the 5A principle.

Abbreviated description of the state of knowledge:

E-cigarettes and heated tobacco products are a new form of delivering nicotine to the human body. Nicotine has a strong addictive potential. Aerosol from an e-cigarette or heated tobacco product is harmful to health. The user of an e-cigarette or heated tobacco product should be treated as a person addicted to nicotine and subject to the same anti-smoking interventions as cigarette smokers.

Summary:

While implementing anti-smoking interventions it is very important to properly identify people addicted to nicotine, record information on nicotine addiction and the way of taking nicotine in the patient'smedical records, and provide basic behavioural support and pharmacotherapy to support the treatment of nicotine addiction, regardless of the form of nicotine intake – cigarettes, e-cigarette or heated tobacco products.

Kaleta D, Świątkowska B, Szulc M, Wojtysiak P, Jankowski M. Interwencja antynikotynowa a e-papierosy i podgrzewacze tytoniu – o czym

należy pamiętać? Rekomendacje dla lekarzy praktyków mających bezpośredni kontakt z pacjentem uzależnionym od nikotyny w zakresie

interwencji antynikotynowej. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2024; 30(2): 81–86. doi: 10.26444/monz/189601

REFERENCJE (45)

1.

Ling PM, Kim M, Egbe CO, et al. Moving targets: how the rapidly changing tobacco and nicotine landscape creates advertising and promotion policy challenges. Tob Control. 2022;31(2):222–228. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056552.

2.

Tehrani H, Rajabi A, Ghelichi-Ghojogh M, et al. The prevalence of electronic cigarettes vaping globally: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Public Health. 2022;80(1):240. doi:10.1186/s13690-022-00998-w.

3.

Sun T, Anandan A, Lim CCW, et al. Global prevalence of heated tobacco product use, 2015–22: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2023;118(8):1430–1444. doi:10.1111/add.16199.

4.

Onwuzo CN, Olukorode J, Sange W, et al. A Review of Smoking Cessation Interventions: Efficacy, Strategies for Implementation, and Future Directions. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e52102. doi:10.7759/cureus.52102.

5.

Martínez C, Castellano Y, Andrés A, et al. Factors associated with implementation of the 5A's smoking cessation model. Tob Induc Dis. 2017;15:41. doi:10.1186/s12971-017-0146-7.

6.

Hajek P, Przulj D, Phillips A, et al. Nicotine delivery to users from cigarettes and from different types of e-cigarettes. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2017;234(5):773–779. doi:10.1007/s00213-016-4512-6.

7.

Jankowski M, Brożek G, Lawson J, et al. E-smoking: Emerging public health problem? Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2017;30(3):329–344. doi:10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01046.

8.

Eshraghian EA, Al-Delaimy WK. A review of constituents identified in e-cigarette liquids and aerosols. Tob Prev Cessat. 2021;7:10. doi:10.18332/tpc/131111.

9.

Szymański J, Pinkas J, Krzych-Fałta E. Elektroniczne papierosy oraz nowatorskie wyroby tytoniowe – obecny stan prawny oraz identyfikacja nowych wyzwań dla zdrowia publicznego. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2022;28(1):95–102. doi:10.26444/monz/147383.

10.

Snoderly HT, Nurkiewicz TR, Bowdridge EC, et al. E-Cigarette Use: Device Market, Study Design, and Emerging Evidence of Biological Consequences. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22):12452. doi:10.3390/ijms222212452.

11.

Tattan-Birch H, Jackson SE, Kock L, et al. Rapid growth in disposable e-cigarette vaping among young adults in Great Britain from 2021 to 2022: a repeat cross-sectional survey. Addiction. 2023;118(2):382–386. doi:10.1111/add.16044.

12.

Balewska A, Raciborski F. „Do-it-yourself” (DIY) e-liquid mixing: users’ motivations and awareness of associated dangers – analysis of social media and online content. Journal of Health Inequalities. 2021;7(1):32–39. doi:10.5114/jhi.2021.107954.

13.

Znyk M, Jurewicz J, Kaleta D. Exposure to Heated Tobacco Products and Adverse Health Effects, a Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6651. doi:10.3390/ijerph18126651.

14.

Jankowski M, Brożek GM, Lawson J, et al. New ideas, old problems? Heated tobacco products – a systematic review. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2019;32(5):595–634. doi:10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01433.

15.

Gallus S, Lugo A, Liu X, et al. Use and Awareness of Heated Tobacco Products in Europe. J Epidemiol. 2022;32(3):139–144. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20200248.

16.

Bekki K, Inaba Y, Uchiyama S, et al. Comparison of Chemicals in Mainstream Smoke in Heat-not-burn Tobacco and Combustion Cigarettes. J UOEH. 2017;39(3):201–207. doi:10.7888/juoeh.39.201.

17.

Farsalinos KE, Yannovits N, Sarri T, et al. Carbonyl emissions from a novel heated tobacco product (IQOS): comparison with an e-cigarette and a tobacco cigarette. Addiction. 2018;113(11):2099–2106. doi:10.1111/add.14365.

18.

Davigo M, Klerx WNM, van Schooten FJ, et al. Impact of more intense smoking parameters and flavor variety on toxicant levels in emissions of a Heated Tobacco Product. Nicotine Tob Res. 2023:ntad238. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntad238.

19.

Jankowski M, Ostrowska A, Sierpiński R, et al. The Prevalence of Tobacco, Heated Tobacco, and E-Cigarette Use in Poland: A 2022 Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4904. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084904.

20.

Balwicki Ł, Cedzyńska M, Koczkodaj P, et al. Rekomendacje w zakresie ochrony dzieci i młodzieży przed konsekwencjami używania produktów nikotynowych. https://pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/... (access: 2024.04.11).

21.

Larsson SC, Burgess S. Appraising the causal role of smoking in multiple diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. EBioMedicine. 2022;82:104154. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104154.

22.

West R. Tobacco smoking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health. 2017;32(8):1018–1036. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1325890.

23.

Wasfi RA, Bang F, de Groh M, et al. Chronic health effects associated with electronic cigarette use: A systematic review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:959622. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.959622.

24.

Mallock N, Pieper E, Hutzler C, et al. Heated Tobacco Products: A Review of Current Knowledge and Initial Assessments. Front Public Health. 2019;7:287. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00287.

25.

Chen DT, Grigg J, Filippidis FT, et al. European Respiratory Society statement on novel nicotine and tobacco products, their role in tobacco control and „harm reduction”. Eur Respir J. 2024;63(2):2301808. doi:10.1183/13993003.01808-2023.

26.

Majek P, Jankowski M, Brożek GM. Acute health effects of heated tobacco products: comparative analysis with traditional cigarettes and electronic cigarettes in young adults. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9(3):00595–2022. doi:10.1183/23120541.00595-2022.

27.

Goebel I, Mohr T, Axt PN, et al. Impact of Heated Tobacco Products, E-Cigarettes, and Combustible Cigarettes on Small Airways and Arterial Stiffness. Toxics. 2023;11(9):758. doi:10.3390/toxics11090758.

28.

Imura Y, Tabuchi T. Exposure to Secondhand Heated-Tobacco-Product Aerosol May Cause Similar Incidence of Asthma Attack and Chest Pain to Secondhand Cigarette Exposure: The JASTIS 2019 Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1766. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041766.

29.

Picciotto MR, Kenny PJ. Mechanisms of Nicotine Addiction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2021;11(5):a039610. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a039610.

30.

Jankowski M, Kaleta D, Zgliczyński WS, et al. Cigarette and E-Cigarette Use and Smoking Cessation Practices among Physicians in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):3595. doi:10.3390/ijerph16193595.

31.

Peterson E, Harris K, Farjah F, et al. Improving smoking history documentation in the electronic health record for lung cancer risk assessment and screening in primary care: A case study. Healthc (Amst). 2021;9(4):100578. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2021.100578.

32.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases,Tenth Revision (ICD-10). https://icd.who.int/browse10/2... (access: 2024.04.11).

33.

Mantler T, Irwin JD, Morrow D. Motivational interviewing and smoking behaviors: a critical appraisal and literature review of selected cessation initiatives. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):445–460. doi:10.2466/02.06.13.18.PR0.110.2.445-460.

34.

Świątkowska B, Jankowski M, Kaleta D. Comparative evaluation of ten blood biomarkers of inflammation in regular heated tobacco users and non-smoking healthy males–a pilot study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:8779. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-59321-y.

35.

Sharma MK, Suman LN, Srivastava K, et al. Psychometric properties of Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence: A systematic review. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30(2):207–216. doi:10.4103/ipj.ipj_51_21.

36.

Broszkiewicz M, Drygas W. Diagnostyka w intensywnych interwencjach leczenia palenia i uzależnienia od tytoniu przy użyciu wybranych testów i teorii rekomendowanych w Polsce – ocena krytyczna badacza. Prz Lek. 2012;69(10):846–853.

37.

Aubin HJ, Luquiens A, Berlin I. Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation: pharmacological principles and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(2):324–36. doi:10.1111/bcp.12116.

38.

Ofori S, Lu C, Olasupo OO, et al. Cytisine for smoking cessation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023;251:110936. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.110936.

39.

Bała MM, Cedzyńska M, Balwicki Ł, et al. Wytyczne leczenia uzależnienia od nikotyny. Med Prakt. 2022;7–8:24–40.

40.

Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD000146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5.

41.

Hajizadeh A, Howes S, Theodoulou A, et al. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;5(5):CD000031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub6.

42.

Burke MV, Hays JT, Ebbert JO. Varenicline for smoking cessation: a narrative review of efficacy, adverse effects, use in at-risk populations, and adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:435–41. doi:10.2147/PPA.S83469.

43.

La Torre G, Tiberio G, Sindoni A, et al. Smoking cessation interventions on health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9396. doi:10.7717/peerj.9396.

44.

Stanel SC, Rivera-Ortega P. Smoking cessation: strategies and effects in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention. Panminerva Med. 2021;63(2):110–121. doi:10.23736/S0031-0808.20.04241-X.

45.

World Health Organization. Tobacco: E-cigarettes. https://www.who.int/news-room/... (access: 2024.04.11).

Udostępnij

ARTYKUŁ POWIĄZANY